At the interface of Lakota and English communications since their historic international meeting about 100 years ago, technical comparisons show similar but diverse ways of getting their meanings across to the other which is easier said than done.

“When one is bilingual, sometimes no will appear yes, and yes no, both remaining reasonable believe it or not. To illustrate, to negative questions in English and Lakota, observe the following changes in comparative answers. First the following example is in English Q and A: Didn’t you understand? No, I didn’t understand. Or… yes, I did understand. Whereas secondly in Lakota replies to the same question, notice the different functions of yes & no: Didn’t you understand? No, I did understand. Or… Yes, I didn’t understand. A Lakota no to no in the negative question results in a positive as in: Didn’t you understand? No, I did understand. In contrast, an English no to no to the same question results in a negative statement as shown earlier. In this snippet Lakota will seem directly easier than English and puzzling it is until one becomes familiar with both conversational modes where either is correct. Yes, we have no prosperity – is easier to understand when you’re fluently Lakota and bilingual.

And thus as we await the bona fide dialogue, we hear the lone voice speaking, day after day, with only the echoes from the canyon walls returning to the speaker. How distant is the person of one language who may be capable only of selfish soliloquies? We wonder if only a person of two languages is near enough to say something – and only bilingual people can respond. In a multilingual world, to speak two languages is to break through the walls of separation and perhaps the only way to open, informed discussion of all issues.

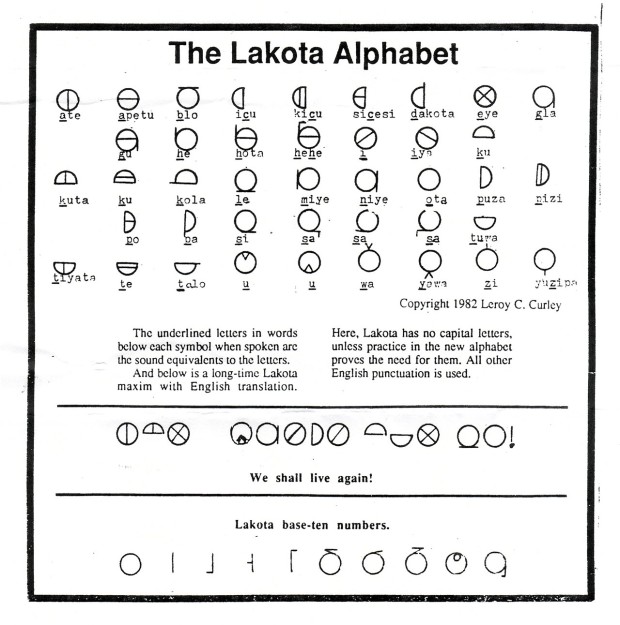

And as we continue to learn two languages, letters in scientific yardstick of “one sound = one letter” show English having in linguist John Malone’s words, a “dumb alphabet.” In that, English has 40 phonemes which are smallest sounds, but writes in 26 letters to communicate laboriously. English 26 letters does not match the 40 sounds in the spoken English. In distinction Lakota letters employing the same yardstick uses 41 copyrighted letters to cover completely the 41 distinct spoken sounds. English letters confuses having to learn unnecessary rules and expensive in time, energy and monies to teach spelling to the children. Through comparing speech sounds, 22 identical sounds in spoken Lakota and English resound clearly. So, would it be true to say that one half of the English language is Lakota and vice-versa?

Presently, Lakota orthography can see no improvement unless English, with cluttered-up ABC’s in a gridlock of e-c-k-s-x letters, is lettered more accurately. However, with this 28th anniversary year of the 41-letter Lakota alphabet with half- and full-moon configurations of circular designs in line-angle differentiations, no other alphabet is like Lakota in 2010. Because, this creation signifies re-unification of the D-N-Lakota speakers in one alphabet with the sounds of D and N included – usable by both Dakota and Nakota speakers and writers besides the Lakota.

And also simultaneously with Lakota 41 letters, the ten symbols assigned to the formerly oral but now written names of base-ten Lakota numbers is of signal development and a gracious gift of the Wakantanka Tunkasila.”—– Leroy Curley, Lakotah Wicasah